Are Ability and Achievement Tests the Same?

Ability and achievement tests are vital tools for identifying gifted and talented students. For students that require ability testing, the Naglieri General Ability Tests™, an ability test by Multi-Health Systems (MHS), uses verbal, nonverbal and quantitative test questions to identify students with high ability. Achievement tests like Renaissance’s STAR Assessments™ measure student proficiency in math, reading, and literacy to identify gifted and talented students1. School psychologists and gifted coordinators rely on information from both tests to ensure students receive instruction and opportunities that best suit their needs, but how do these tests compare? In fact, are they the same?

How are ability and achievement tests similar?

Ability and achievement tests measure a student’s skills and knowledge (to some extent) and are often used together to assess a student’s strengths. Both types of tests assess cognitive skills, require problem- solving, and compare a student’s performance to other students of the same age or grade level. Both are standardized assessments, meaning they are administered and scored consistently across all test-takers. This standardization ensures that the results are reliable and comparable. Additionally, both ability and achievement tests provide valuable insights into a student’s strengths and weaknesses, helping educators and school psychologists tailor their instruction to meet individual needs. At the same time, these practitioners use the tests to identify areas where students excel or may need support2.

How are ability and achievement tests different?

The key difference is what they measure. Where ability tests assess a student’s potential to learn and general ability and are designed to predict future academic success, achievement tests measure what a student has already learned and their mastery over the material taught in school3, allowing students to demonstrate what they know after explicit instruction.

How are ability and achievement tests related?

Research has explored the question of how ability and achievement tests relate to one another for decades, and findings tend to converge on the link between general ability tests and future success, in terms of academic achievement and occupational success4. Yet, general ability (and specific types of intelligence) tests and academic success are not fully overlapping or redundant; they each offer a unique look at a student’s skills and predict student outcomes in different ways and may, in fact, influence one another5. There are many factors that contribute to academic success, and general ability is an important, but not singular, factor.

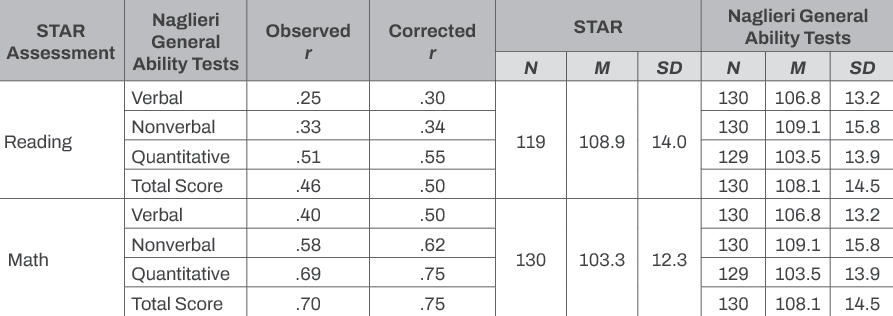

To further explore the relationship between ability and achievement, MHS recently conducted a study using the Naglieri General Ability Tests and Renaissance’s STAR assessments. With a sample size of students in Oregon ranging from 119 to 130 across the different tests, students in 2nd through 6th grade completed both sets of the Naglieri General Ability Tests and the Renaissance’s STAR assessments in their classroom setting, with approximately four weeks between the ability and achievement tests. Standardized test scores were used to streamline analysis and comparison, and students’ scores were calculated relative to their same-age and same-grade peers. Results are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Correlations between the Naglieri General Ability Tests and Renaissance’s STAR Assessments.

Note. N = 119 to 130 Grade 2 to Grade 6 students. Correlations were corrected for variability in range6. Guidelines for interpreting |r| very weak < .20, weak = .20 to .39, moderate = .40 to .59, strong = .60 to .79, very strong ≥ .80. Naglieri–V = Naglieri General Ability Tests–Verbal; Naglieri–NV = Naglieri General Ability Tests–Nonverbal; Naglieri–Q = Naglieri General Ability Tests–Quantitative.

As expected, correlations between the Naglieri General Ability Tests and the Renaissance’s STAR assessments were positive, ranging from weak-to-strong relationships. The Naglieri suite of tests does not require reading comprehension skills, and therefore, its relationship to a test evaluates reading achievement was not expected to be very strong. When comparing the STAR Reading assessments with the Naglieri General Ability Tests, corrected correlations ranged from .30 to .55. (For full results, including raw correlations, see Table 1.) These weak-to-moderate correlations highlight that general ability is a skill critical to success in both types of tests; however, it is worth noting the differing extents to which ability is central to the test success and that the Naglieri General Ability Tests require very limited English-language comprehension skills, so explicit reading skills are not measured or required (in contrast to the STAR Reading assessment that is explicitly assessing reading ability). On the other hand, the relationship between the STAR Math assessment and the Naglieri General Ability Tests ranged from .50 to .75; these correlations can be described as moderate to strong. These types of tests were expected to show some degree of positive correlation because numeracy and mathematics skills, such as multiplication, are both explicitly taught as part of academic curricula and are bolstered by general ability; therefore, a student is likely to perform somewhat similarly on both quantitatively focused ability and achievement tests.

Overall, the Total Score for the Naglieri General Ability Tests (comprising performance across the three tests: Quantitative, Verbal, and Nonverbal) was moderately correlated with the STAR Reading assessment (r = .50) and more strongly related to the STAR Math assessment (r = .75).

Table 1. Detailed Results.

Note. Correlations were corrected for variability in range5. Guidelines for interpreting |r|: very weak < .20, weak = .20 to .39, moderate = .40 to .59, strong = .60 to .79, very strong ≥ .80. Students ranged from Grade 2 to Grade 6, with a mean age of 9.8 years (SD = 1.5), and 51.5% of the sample was female.

The complementary roles of ability and achievement tests

The findings from our recent study reflect stable trends in the research; other studies have also observed moderate correlations between ability and achievement tests, averaging around .50 (i.e., explaining only about 25% of the variability between the two tests)6,8. Studies have shown that the correlation between ability and achievement tests can vary in strength, and the relationship can depend on certain subject areas, the type of intelligence tests used, and the student’s motivation and engagement (where highly engaged students tend to perform better on both types of tests)7, 8,9.

The similarities and differences between ability and achievement tests, and their intricate relationship, are crucial for effective gifted identification and the evaluation of student abilities. Educators can gain a comprehensive understanding of a student’s general ability and academic skills (i.e., areas to leverage or develop based on achievement test results) by integrating data from both types of assessments, ultimately supporting their growth and development by providing the appropriate support and instruction. While general ability can predict student achievement in primary education, prior academic achievement becomes a strong predictor of future achievement in secondary school years8, demonstrating the utility of understanding a student’s skills, learning experiences, and potential through standardized evaluations.

Visit our storefront and learn more about the Naglieri General Ability Tests.

References

1 Renaissance STAR Assessments. (2017). Renaissance Learning, Inc.

2 McGrew, K. S. (2009). CHC theory and the human cognitive abilities project: Standing on the shoulders of the giants of psychometric intelligence research. Intelligence, 37(1), 1–10.

3 Naglieri, J. A., & Ronning, M. E. (2000). The relationship between general ability using the Naglieri Nonverbal Ability Test (NNAT) and Stanford Achievement Test (SAT) reading achievement. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 18(3), 230–239.

4 McCoach, D. B., Yu., H., Gottfried, A. W., & Gottfried, A. E. (2017). Developing talents: A longitudinal examination of intellectual ability and academic achievement. High Ability Studies, 28(1), 7–28.

5 Dahlke, J. A., & Wiernik, B. M. (2019). psychmeta: An R package for psychometric meta-analysis. Applied Psychological Measurement, 43(5), 415–416.

6 Sternberg, R. J., Grigorenko, E., & Bundy, D. A. (2001). The predictive value of IQ. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 47(1), 1–41.

7 Yildirim-Erbasli, S. N., & Gorgun, G. (2024). Disentangling the relationship between ability and test-taking effort: To what extent the ability levels can be predicted from response behavior? Technology, Knowledge, and Learning, 1–23.

8 Best, J. R., Miller, P. H., & Naglieri, J. A. (2011). Relations between executive function and academic achievement from ages 5 to 17 in a large, representative national sample. Learning and Individual Differences, 21(4), 327–336. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2011.01.007

9 Sergiou, S., Georgiou, G. K., & Charalambous, C. Y. (2021). Examining the relation of Cognitive Assessment System-2: Brief with academic achievement in a sample of Greek-speaking children. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 11(1), 86–94.